Companies earn millions offering cash advances to heirs, with effective interest rates as high as 490 percent

Soon after John R.’s mother died in April 2018, he began the process of settling her estate—consisting primarily of her San Francisco home—by notifying his eight nieces and nephews that they were entitled to a piece of an estimated $2 million inheritance.

Normally, it would take a year or two for beneficiaries to receive their payout. But that wasn’t the case here.

Weeks after the estate was entered into probate court—a legal process that ensures that a deceased person’s debts are paid and assets distributed to the right beneficiaries—one niece got a cash advance of $15,000 from a company called Advance Inheritance. In return, she assigned $25,000 of her expected inheritance to be paid to Advance when the probate case eventually ended.

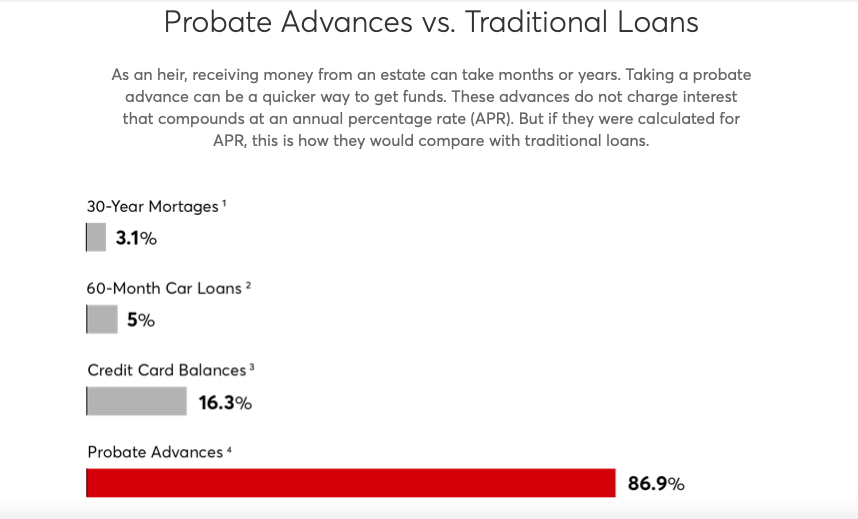

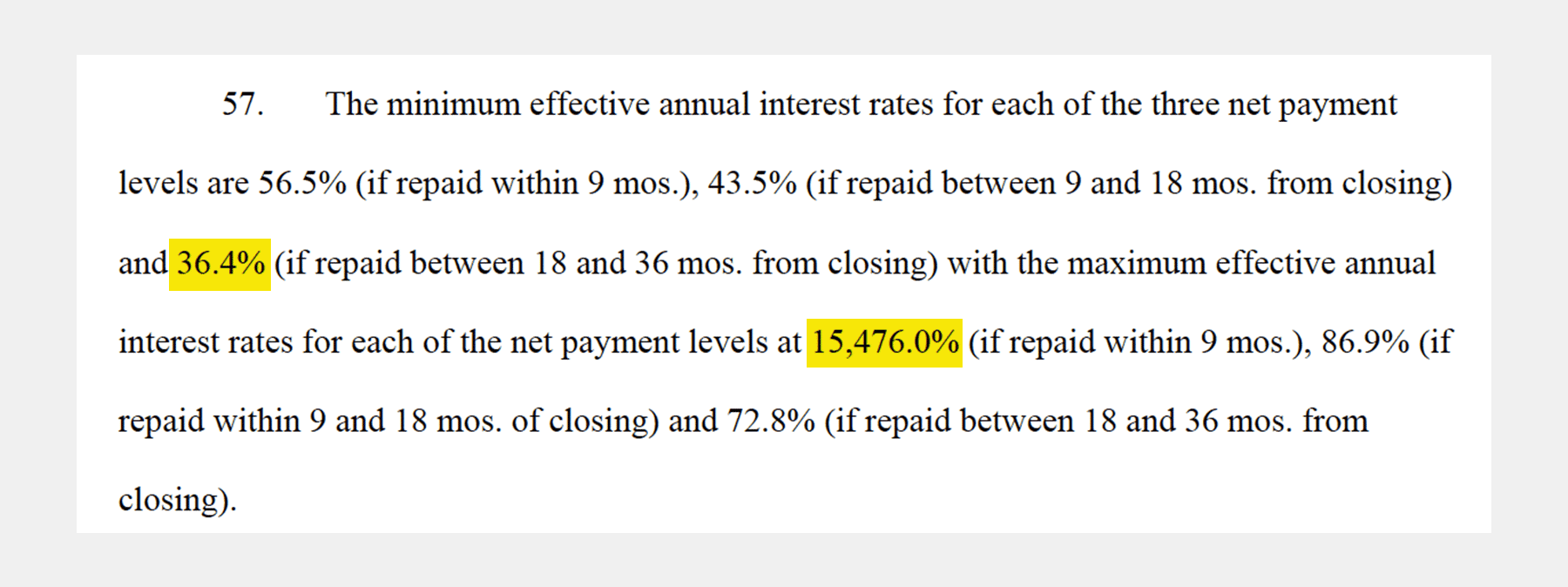

By the time the estate was cleared by the court two years later, family members had obtained $282,000 combined in cash advances through 22 different transactions with four companies. If the transactions had been traditional loans, the annual percentage rates (APR) would have ranged from 36 to 248 percent. The companies received about $481,800 combined when the probate case settled—a markup of 70.9 percent.

The story of John R.’s family and their estate, culled from a review of hundreds of pages of court documents, is not an anomaly. Thousands of Americans have obtained upfront cash advances against a portion of their inheritances from relatively obscure businesses that receive larger sums in return once the estate is settled, a Consumer Reports investigation found.

Whether it’s because people who get those cash advances are unable or simply unwilling to wait for the probate process to be completed, the arrangement comes at a significant cost, according to CR’s analysis of nearly 240 transactions involving about 100 beneficiaries in eight states. Advances ranged from $2,000 to $75,000 in those cases, and beneficiaries gave up, on average, nearly half of what they would have otherwise inherited. Calculating for APR, as a loan would be, one in four of the closed transactions hit triple-digits. One was 490 percent. (Read more about CR’s analysis.)

Unlike other controversial financial options that have popped up in the last decades targeting financially strapped Americans—such as payday loans, tax refund anticipation loans, and litigation loans—probate advances have flown under the radar. While some financial products with sky-high interest rates have been subjected to intense scrutiny by federal and state lawmakers, and in some cases have been outlawed, the probate advance industry has received little regulatory oversight.

“This is a problem of policy,” says David Horton, a law professor at the University of California-Davis who has studied probate advances and has raised significant questions about the business.

1. Freddie Mac, 2020.

2. U.S. Federal Reserve, 2020.

3. U.S. Federal Reserve, 2020.

4. CR analysis of 168 probate advances from seven states (PDF).

The industry, which has advanced millions of dollars over the years, says it’s providing a service to those in need of cash to pay for everything from past-due property taxes to medical bills. Indeed, many customers appear grateful for the business in online reports and company reviews.

“We are proud of the service we provide and the highly ethical way we conduct our business at IFC,” says Doug Lloyd, chairman and CEO of Inheritance Funding Company, which began providing advances to probate beneficiaries in 1992 and claims to have advanced more than $200 million to customers to date. He emphasized that, given the number of risks companies like his take on, “It is easy to understand why banks and other financial institutions are not in this business.”

Companies in the industry also say that they provide advances, not loans—a crucial legal distinction. If they were making loans, their service would be subject to usury laws prohibiting high interest rates and to requirements under the Truth in Lending Act about disclosing the arrangement’s true cost.

“We don’t calculate APRs for these transactions because that would be impossible to compute accurately, in advance, when the payoff date is unknown,” says Robin Shapiro, CEO of ProbateCash, a relative newcomer to the industry. “We think it would be a confusing and potentially misleading measure when applied to a transaction that is simply not a ‘loan.’”

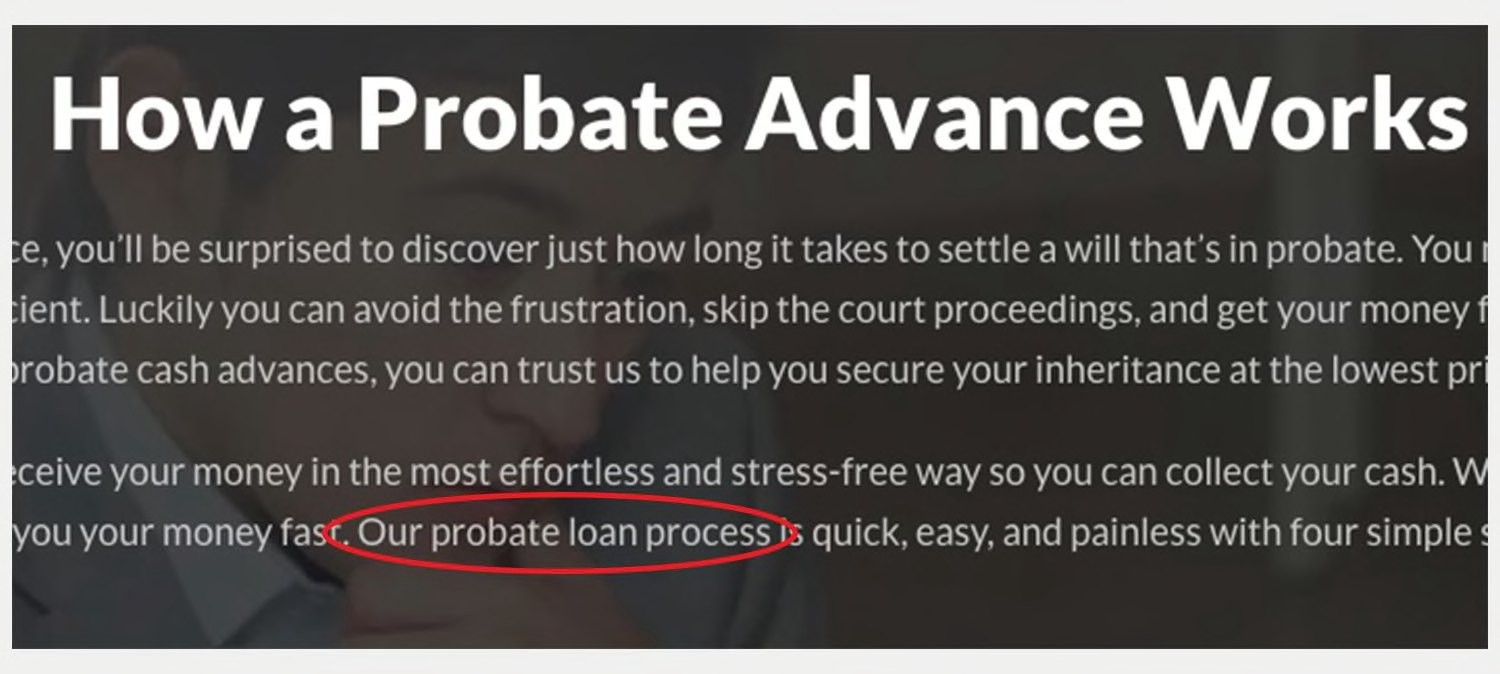

Consumer advocates and critics, like Horton, disagree. And indeed, whether the companies offer loans or advances is not so clear. At least two probate companies include “loan” in their name, for example. In some cases, companies also appear to secure deeds to the homes in the estate as collateral, which is typical of loans. IFC, perhaps the largest company in the field, had until very recently touted online how easy its “loan process” is.

Moreover, some consumer advocates point out that there’s a long history of fringe lenders trying to evade predatory lending laws by arguing that their product is unique and exempt, when it isn’t.

“It makes me very suspicious when somebody trying to sell a loan product says, ‘Oh, we don’t have to call it a loan,’” says Paul Bland, executive director of Public Justice, a public interest legal advocacy group. Payday lenders historically argued they weren’t providing loans, rather just “charging a fee for check cashing,” Bland says.

Easy Money

Whether loans or advances, legal experts and consumer advocates say the industry is making huge profits, sometimes by soliciting clients that they’ve identified through court filings, including people who are not only financially vulnerable, but emotionally, too, following the death of a loved one.

Probate advance companies have also been known to approach people by mail. Shortly after the untimely death of her daughter in 2004, one California woman reportedly got a letter from a company offering cash up front in exchange for the proceeds of her daughter’s estate. She was appalled. “These people are hearse chasers,” she told a San Francisco Chronicle columnist at the time.

When UC-Davis professor Horton began to study probate advances in 2016, he and UC-Davis law professor Andrea Cann Chandrasekher analyzed hundreds of probate cases in Alameda County, Calif. They found the effective APRs of many deals exceeded 50 percent, with nearly three dozen eclipsing 100 percent. He also found that probate advances were made against 5 percent of all estates they analyzed.

A follow-up study Horton is slated to publish this year with Reid Weisbord, a professor at Rutgers Law School, examined cases in San Francisco County between 2014 and 2016 and had similar findings. Companies advanced about $2 million to beneficiaries there and received about $3 million in return. The average effective APR was 127 percent.

CR’s analysis of probate advances in eight states shows that it’s not just in California that consumers experience such high costs.

In our review, beneficiaries received $2.53 million in total in cash advances. In return, they agreed to give up $4.51 million to a group of several companies—a markup of 78 percent. On average, consumers gave up 45 percent of what they were due.

A handful of cases dragged on for several years, producing effective APRs as small as 5.5 percent. But the average APR in the completed cases CR reviewed was 86.9 percent, and ranged as high as 490 percent. More than 45 advances in completed probate cases had an effective APR exceeding 100 percent.

“These products are targeted at grieving families, can have high effective interest rates, and may be laden with fees. Yet, there appears to be little oversight of these companies.”

CHRISTINA TETREAULT

Manager of financial policy at Consumer Reports

CR’s repeated requests for an interview with IFC went ignored until last week, when the company’s general counsel inadvertently copied a reporter on an email to its board of directors, acknowledging our effort.

“IFC has found it impossible to accurately quantify and forecast an average rate of return because of the constant fluctuations of new fundings, pay offs, and write-offs,” says Lloyd, IFC’s CEO and chairman. “In particular, losses vary widely in different jurisdictions. Beyond that, IFC’s estimated yields are proprietary competitive information we are not willing to divulge publicly.”

Shapiro, of ProbateCash, believes it would be inappropriate to apply disclosure rules and rate caps, designed for products with fixed terms, to probate transactions with an uncertain payout date. He notes that probate advance contracts typically state exactly what a customer receives in upfront cash, and exactly what they will be giving up when the estate eventually pays out.

“In our experience, that’s what our customers want to know and that’s what we tell them,” he says.

But in some contracts from other companies that CR reviewed, those amounts weren’t included; in others, beneficiaries were also charged fees for obtaining an advance.

“These products are targeted at grieving families, can have high effective interest rates, and may be laden with fees,” says Christina Tetreault, manager of financial policy at Consumer Reports. “Yet, there appears to be little oversight of these companies.”

Risky Business?

Probate advance companies say their business model is justified because of the financial risk they take. Because the probate process is slow, and previously unknown debts may emerge during it, years may pass before they’re repaid—if ever.

And they say their repayment depends on the estate remaining solvent by the time the case wraps up. ProbateCash’s Shapiro says the company has lost money providing advances in cases where an estate’s debts turn out to be more than expected, or when a beneficiary lies about their identity.

“Obviously, we spend time and money in an effort to avoid those situations and mitigate those risks,” Shapiro says. “But unlike lending, where one can secure a borrower’s obligation with liens, or mortgages, and pursue recourse directly against a borrower, these transactions are investments in situations with uncertainty as to when or whether one gets repaid, and little or no recourse if we don’t.”

The probate process can indeed be sluggish, legal experts say. The executor of the estate has to pay off the deceased’s debts, sell real estate assets, and track down relatives. If there is no will, matters can be especially complicated. Marilyn Monroe’s estate famously took 40 years to clear probate.

“In almost all cases, with rare exceptions, the lender not only gets their advance back, but also gets a huge markup.”

DAVID HORTON

University of California-Davis law professor

But it’s rare that estates take that long to wind through the probate process. Generally, cases are completed in one to two years, says Weisbord from Rutgers, who is an expert in probate and estate law.

And in his analyses of probate advance contracts from Alameda County, Horton determined that the risk for companies is very low. They recouped their entire investment 97.5 percent of the time, he found.

ProbateCash says its experience has been worse. The company has yet to recoup on about a quarter of the advances it made between March 2018 and February 2019, Shapiro says. IFC declined to provide that company’s current loss rate, saying it was proprietary information.

But Horton’s number is in line with figures previously touted by IFC. In 2009, the company advised prospective investors its historic losses since inception were “less than 2 percent,” according to documents obtained by CR. The deals in San Francisco that Horton and Weisbord reviewed performed even better for the companies.

“In almost all cases, with rare exceptions, the lender not only gets their advance back, but also gets a huge markup,” Horton says.

Look Like a Loan, Regulate Like a Loan?

Jeremy Kidd, associate professor at Mercer University School of Law in Macon, Ga., says it’s “completely valid” to view probate advances with suspicion. But he argues there are plenty of explanations for why a beneficiary would accept the terms that companies offer.

Maybe they don’t want to be involved in the probate proceedings because of family dynamics, have pressing financial obligations, or simply don’t want to wait for the estate to clear probate court. Unless there’s evidence of illegality on the part of the industry—such as the beneficiary being coerced, defrauded, or put under duress—then Kidd says he has no problem with the arrangement. Kidd published academic articles in 2018 and 2019, criticizing Horton’s work, arguing it unfairly characterizes the products as loans.

“I have to presume the individual had a reasonable interest to sell their property at that rate,” he says.

But even so, there are reasons to regulate probate advances like loans, says CR’s Tetreault. “These products have the hallmarks of a loan: cash now to a borrower, with a promise of a higher repayment amount later,” she says. “Given that, there is no reason why the rules governing lending shouldn’t apply.”

Courts have weighed in only once on the question of whether the probate advance companies offer traditional loans.

In 2011, a federal judge sided with the industry, ruling that 21-year-old San Diego resident Jonathan Reed didn’t incur debt when he obtained a cash advance from Advance Inheritance and that the company was therefore exempt from lending requirements under the Truth in Lending Act.

Reed obtained the advance in 2010 to pay off past-due property taxes on the house owned by his father, who’d passed away several years earlier, according to his complaint. Reed, the sole heir to the estate, continued living there, and alleged the advance led to a spiral of insurmountable debt.

Reed could not be reached for comment. But Dan Lickel, an attorney who represented Reed, says lawmakers should consider subjecting probate advances to the kind of disclosure requirements that apply to consumer loans.

“I think folks who are receiving an inheritance need to understand the cost of entering into a transaction like this,” he says, “especially where the likelihood of ultimate delivery of the inheritance is really not in doubt, and the person receiving the inheritance is unsophisticated in financial matters.”

Advance Inheritance, which denied the claims but reached a settlement with Reed over the allegations, did not provide answers to a list of questions from CR.

If pressed in court, probate companies could cut their losses rather than argue for their legitimacy. That’s what Inheritance Funding Company did in 2013, after New Hampshire resident Chad Preston filed for bankruptcy.

Preston, records show, obtained a $25,000 advance from IFC in return for a $52,300 interest in a home he co-owned with five siblings that was sold as part of a probate court proceeding.

The trustee of Preston’s estate alleged in a lawsuit filed against IFC that the advance was “in reality a loan” that violated New Hampshire state lending laws, with an exorbitant effective APR. Lloyd says IFC disputed the allegations in the lawsuit but settled to avoid further costs and agreed to be paid just $25,000—the same amount as the initial advance.

Richard McPartlin, an attorney who represented the bankruptcy trustee in the suit, says the advance from IFC “didn’t strike me as being a real good deal for Mr. Preston, obviously.”

“There are a decent number of folks who lend to people who really need money whose tactics I tend to find questionable,” McPartlin says.

Horton set off the debate over what to call the cash advances in 2016, when he co-published his first study examining the industry in the Yale Law Journal with the simple title “Probate Lending.” The study made clear that Horton understands the significance to the industry of their product being treated by regulators as a loan. But with so many fringe financial products—like payday loans or litigation loans—already described in the public that way, he thought the title was innocuous.

“All of these products are described as loans,” he says. “The truth is, I wasn’t really trying to poke the bear at all. I was just trying to be descriptively accurate.”

Even IFC, despite insisting that it doesn’t issue loans, has conflated the definitions. The company’s website prominently advertised until very recently that IFC can offer “fast & easy inheritance loans,” and also advised consumers about how its “probate loan process” works.

Last week, after CR had inquired repeatedly for an interview with company officials, IFC removed the reference to the company’s “loan” process on its website.

Lloyd blamed the issue on outside consultants working on the company’s website, who he says “recently introduced loan language” to attract customers.

“We learned of this issue some weeks ago and this issue has now been rectified,” he says. “We’ve also added disclaimer language to every page of our website making extremely clear that IFC is not a lender and our services are not loans.”

What to Know

Probate lawyers and experts advise that if you are a beneficiary to an estate and can wait for it to be paid out, you should.

Much depends on where the deceased lived, as probate laws vary greatly state to state, says Gerry Beyer, a Texas Tech University School of Law professor and expert in probate law. That may explain why the probate advance industry seems to be concentrated in California, where the legal process is especially complicated.

Lisa Fialco, a probate, trust, and estate planning attorney who practices in California and has written for legal publisher Nolo, says probate can be “bewildering” to beneficiaries and that educating yourself about the process can be an immense help.

“If somebody doesn’t necessarily know how long probate will take, what the involvement will be from them, it may seem like they’re in a much better situation if they take less money now rather than wait out the process,” Fialco says. “Whereas, if they know more about the process, they might be able to make a better educated decision.”

Horton—a former practicing probate attorney himself—has offered a number of proposals to increase regulation of the probate advance industry. In particular, he thinks policymakers should mandate that companies lower the effective APR of their products, or courts should require them to.

“I don’t oppose this industry at all, and, I think, if done right, it could actually serve a need,” he says.”

In California, the only state with a law regulating probate advances, judges are already authorized to weigh in and invalidate an advance if the assessed fees or charges are “grossly unreasonable,” if they choose. Horton says they should be required to conduct a review of each advance. Other jurisdictions should consider collecting data on the business, he says, and suggests expanding the judicial oversight into other states or at the federal level.

He also suggests that lawmakers apply Truth in Lending Act provisions to probate advances, providing more transparency to consumers. Companies could also be required to automatically reduce the effective APR to the maximum permissible rate in a state and adjust how much it is repaid accordingly. It would make the business less profitable, Horton says, but it would also address concerns about fairness.

If you need to take out a probate advance, Horton advises shopping around “because it seems very little of that goes on, and I think companies should be forced to compete with each other.”

But otherwise, he says, a consumer considering a probate advance who doesn’t absolutely need one should steer clear: “I would say run, don’t walk away.”